One thing is for sure, Covid-19 has destabilised everything that has previously been deemed as normal. For governments, for businesses, for people—navigating this new virus has been like fumbling through the dark and we still see uncertainty on a daily basis. When is it safe for people to return to work? When is it safe to visit a cafe? When can shops reopen and what measures should they take to protect customers? How should property owners and managers safeguard their buildings and will this pandemic change our urban environments for good?

In this instance, Asian cities can offer us a guiding light. Previous outbreaks, such as SARS in 2003, led to permanent and important changes in cities like Hong Kong. Temperature checks and health declarations became the norm at the airport; increased epidemiology training across all public health service providers; plus an increase in isolation facilities at hospitals (Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, 2015). Hong Kong’s post-SARS actions provides an essential blueprint from which countries may improve, adapt or utilise for Covid-19.

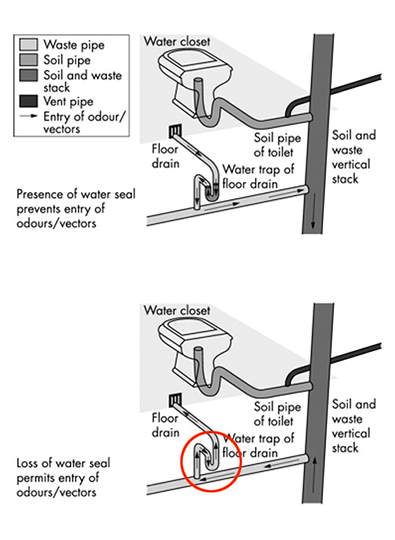

In 2003, poor design and improper building management led to 321 residents becoming infected with SARS at Amoy Gardens Apartments in Hong Kong (Department of Health, 2003). Upon inspection, it was discovered that a high number of drain U-traps in Block E were depleted or dry allowing the airborne virus to flow freely between apartments — literally through the drain pipes. The simple act of lifting a toilet seat or switching on the exhaust fan was enough to draw contaminated air into each bathroom.

The Hong Kong Department of Health acted quickly. After a thorough cleansing and disinfection of Block E, residents were promptly informed about how to properly clean and maintain their sinks, bathtubs, toilet bowls and the all-important floor drains. This advice was then extended to all people in Hong Kong when the government released a physical guide on how to clean and disinfect your home.

During and after SARS, environmental hygiene became a priority and pest control was stepped up across the city for the long-term. Property owners and management companies were instructed to properly maintain and repair drainage and sanitary systems which set a benchmark for all future developments (Department of Health, 2003).

SARS did not spell the end of crowded urban areas or skyscrapers, nor will Covid-19, but this most recent virus will undoubtedly bring its own set of unique challenges for urban environments and office buildings. A recent article by Ben Tranel at Gensler suggests that further industry wide standards will emerge. Much like the WELL Building Standard®, these will deem buildings to be ‘healthy’ or not by meeting a variety of criteria such as air, water, nourishment, light and comfort (Tranel, 2020).

In the short-term, the heightened focus on personal hygiene and social distancing is likely to fade from memory. Visitors will be looking to property owners, developers and managers to prove the safety of their spaces, particularly in China where trust is hard-earned. Much like in post-SARS Hong Kong, the visible and regular disinfecting of common areas (kitchens, bathrooms, lifts, lobbies, etc) will become common practice in the workplace. And the regular reporting of disinfection to building occupiers either by digital or physically means will be essential. This may even extend to public facilities such as buses, underground train networks and public seating.

The good news is that smart design can decrease the rate of sickness, alleviate symptoms of illness, and improve mental functions, outlook, and mood. (Tranel, 2020)

Architects and designers are ready to ‘design out dangers’ of viruses in the future with a focus on air ventilation and filtration design for airborne viruses as well as self-cleaning or ‘easy to clean’ materials. Comparing Hong Kong’s MTR train carriages to London Underground’s historical design, we can see how the Hong Kong design supports commuter safety better with improved air circulation, washable seats and spacious cabins.

In the long-term, many cities will learn their own Covid-19 lessons. However to gain a short-term advantage the world should take heed from the lesson already learned in Asian cities such as Hong Kong, Shanghai and Singapore.

Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (2015), “Checklist of Measures to Combat SARS”, Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region [Online]. Available from: https://www.info.gov.hk/info/sars/pdf/checklist-e.pdf (Accessed on: 7 May 2020)

Hong Kong Department of Health (2003), “Outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) at Amoy Gardens, Kowloon Bay, Hong Kong — Main Findings of the Investigation”, Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region [Online]. Available from: https://www.info.gov.hk/info/sars/pdf/amoy_e.pdf (Accessed on: 7 May 2020)

Tranel, B (2020), “How Should Office Buildings Change in a Post-Pandemic World?”, Gensler [Online]. Available from: https://www.gensler.com/research-insight/blog/how-should-office-buildings-change-in-a-post-pandemic-world (Accessed on: 7 May 2020)

TAGGED: